As we light the final candle of Advent and this season draws to a close in the celebration of Christ’s birth, I think it only appropriate to reflect for a moment on what it means to worship the Christ, born as a human child, the very embodiment of God, in a world dominated by fear. As we have listened to politicians attempt to debate their way into the 2016 presidential primary, there has been a strong overcurrent of fear. Fear that our way of life is at stake, fear that by somehow accepting the “other” of Muslims refugees and even our own Muslim neighbors here in the U.S. we are putting our own self – our identity in Christ – at risk. And it has been in the midst of all this fear that a particular event has pierced the Advent reflection of so many Evangelical Christians, creating a season of controversy that has created division and animosity even among those who would otherwise consider themselves brothers and sisters in Christ.

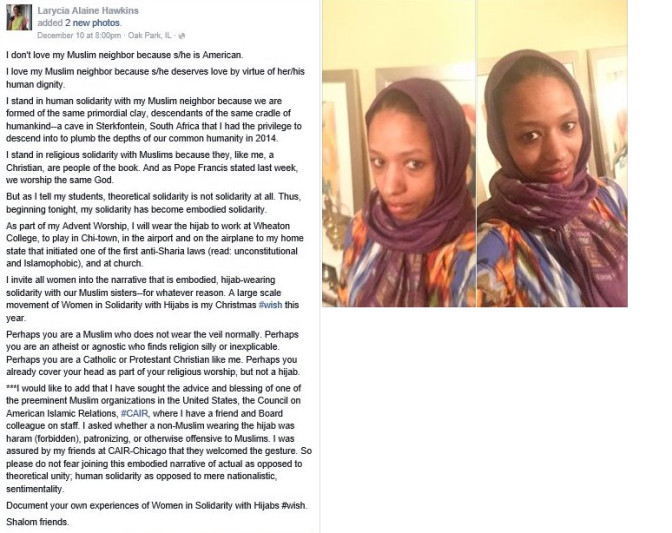

On December 10, 2015, Wheaton College Associate Professor of Political Science Dr. Larycia Hawkins made the following statement on her private Facebook page.

Since this post, Evangelical Christianity has erupted, bursting at the seams with a variety of responses to her words. Most notable among the responses has been Wheaton College itself, which suspended Dr. Hawkins on December 15, placing her under review to determine if her statement met the criteria of their statement of faith and community covenant.

Since the suspension, both Hawkins and Wheaton have expressed a desire to resolve the issue, though it seems all talks are currently at an impasse. Wheaton has asked Dr. Hawkins to clarify her statement, but apparently remains unsatisfied with her answer. She has even offered public statements on her beliefs which seem to be unsatisfactory for Wheaton’s review process.

Initially, I had no intention of adding my voice to the conversation. However, over the last 24 hours, my participation in a conversation on the Facebook page Biblical Christian Egalitarians has made me realize that there is still something to be added to this conversation.

Preliminary Concerns

Before I begin, I want to lay some groundwork here. First, I want to be clear what I am, and am not, endeavoring to say here. I am not going to, here, make an argument over whether or not Wheaton’s actions are intended to specifically target the Muslim community. If you are looking for such a post, see here. Nor will I attempt to discern whether Dr. Hawkins statements truly violate the standards Wheaton claims. I have my opinions on the matter, but the truth is I am not a member of the Wheaton faculty, staff, or community and it ultimately will prove a fruitless endeavor for me to engage that line of reasoning. Thus, my only intention here is to take a moment to analyze the actual statements Dr. Hawkins has made.

Second, I want to lay out clearly the criteria I will use to analyze this argument. If you want a full explanation of why I use these criteria, I refer you to this post. My criteria are as follows:

- Is the argument rhetorically consistent?

- Is the argument supportable with Scripture?

- Is the argument Christ-like?

Rhetoric

I want to take a moment to analyze precisely what Dr. Hawkins has said. She has stated that, as an act of solidarity with her Muslim neighbors and friends in an American setting, she chose to wear a hijab. For her, the hijab is a symbol that she has chosen to live out her faith in the Advent season. She desires to step outside the harmful and, frankly, xenophobic rhetoric that seems to have infected the political arena and social media.

As such, Dr. Hawkins decided to wear a hijab for advent, to embody solidarity. She has noted that, because of her skin color and gender, some who have seen her have assumed her ethnic and religious identity based simply on appearance. She has endeavored to understand the anti-Islamic rhetoric endemic to the American public arena by placing herself in their shoes.

In doing so, Dr. Hawkins made a profound statement which is really at the center of all the controversy. She dared to claim that, at their heart, Islam and Christianity worship the same God. This is, of course, a claim which can be expected to rub some the wrong way. But, the question is, is there anything about the claim which does not hold up to scrutiny.

First, it ought to be noted that the word “Allah” is, in all reality, nothing more than the Arabic word for God. Its use predates the rise of the Islamic religion and even has occurred in ancient translations of Christian Scripture. Further, the word is still used by many Christians around the world (for instance, see here and here). In that sense, then, the common word usage may suggest that Dr. Hawkins has a point to make.

Second, both Islam and Christianity (along with Judaism) are religions which claim to have descended from the biblical character Abraham. However, while Christianity claims its roots through Abraham’s son Isaac, Islam claims to carry the tradition of his rejected son Ishmael. Nevertheless, both claim to worship the God of Abraham. This is important because the biblical text itself states that God promised Ishmael’s mother, the slave-wife Hagar, that he would multiply her offspring in the same fashion as promised to Abraham through Isaac (Gen 16:10, cf Gen 12:1-3) and gives the etymology of Ishmael as “the Lord has given heed to your affliction” (v. 11). She called this God El-roi (the God who sees). This God was the God of Abraham.

Now, it is notable that the word given Hagar also suggested that the descendants of Ishmael would live at odds with their kin (v. 12). But the God who saved Hagar and Ishmael in their time of need, who promised to multiply Ishmael’s line is none other but God as revealed in the OT, the one who would reveal himself as YHWH to Moses.

A further note that must be made, Dr. Hawkins has claimed this God is the “same” as Allah, she has not called the God of the Bible identical to Allah. This is an important distinction that many seem to overlook. It is possible to be the same as something or someone but still be distinct. It entirely depends on the criteria for “same-ness”. For instance, my wife and I are both of Caucasian descent. We both have the same last name. We are both parents of the same children. In all these things I could, genuinely, claim my wife and I are the same. On the other hand, my wife is female, I am male. My wife is of Polish and Lithuanian descent, while I cannot trace my family tree in such a distinct fashion. I am a stay at home parent while my wife works full-time. My wife and I are in many ways the same, yet we are also profoundly distinct individuals who cannot simply be equated.

For this reason, it is notable that Dr. Hawkins has stated she is claiming “same” as a word which implies solidarity in adversity. She does not mean to make a theological statement of equivalence. She is not ignoring the distinct particularities which differentiate the Islamic and Christian religions. She is, however, noting that there are reasons to stand beside the Muslim community in times of oppression and to recognize those things we hold in common in attempt to love and care for our neighbor in praxis, and not simply with lip service; and that this is consistent with the call to worship and reflect on the Christmas event during the advent season.

Scriptural Precedence

In the section above, I noted the incident with Hagar and the God of Abraham. There is an important Scriptural precedent in this passage which occurs throughout the Pentateuch. That is, Hagar uses a name for God rooted in the name El. El is the name of the supreme deity and creator god in the Canaanite pantheon of the second millennium BCE.[1]

This is no coincidence. As we know from Scripture, Abraham himself was called to leave his father’s family and live among the Canaanite peoples (Gen 11:31-12:3). Further, the Israelite religion shows some remarkable parallels with its Near Eastern neighbors – similarities between creation and flood narratives for instance – that suggest that there was some interaction between how the Israelites formed their beliefs about God and the way their neighbors conceived deity. Given that the Israelites, throughout Scripture, prove themselves to be polytheistic – even if their God YHWH had clearly commanded otherwise – it stands to reason that many of the oldest traditions in Scripture would include this name.

Further, it stands to reason, given what we know of God in Scripture, that he would reveal himself first in categories familiar to those with whom he wished to enter relationship. He chose a name that would be known, El, to establish the relationship and chose to reveal his personal and self-defining name in the pivotal even that was the burning bush, YHWH. This is a consistent theme in Scripture, the God who self-limits, who in love makes himself profoundly imminent and relatable in order to gradually reveal himself to his people.

In fact, there is not greater example of this than Jesus. Jesus is the divine Logos incarnate, the full revelation of the Father (John 1:1-18). Yet, he does not reveal himself as God all at once, but is in fact only truly perceived as God truly after the events of his resurrection, when he explains everything to his disciples on the Emmaus road (Luke 24:13-35). Paul chose to describe this as the kenosis of Christ, the self-limiting God who became mortal, became sin, embraced death and abandonment on the cross (Phil 2:1-11, 2 Cor 5:21, Matt 27:46). This God not only knows our story, he participates in it, he shares it (Isa 52:13-53:12).

So, it is no stretch to say that God can reveal himself to people who initially worship him falsely under the name of another deity. If YHWH can also accept the name El from the persons who wrote Scripture in reflecting on their own history of unfaithfulness to God in polytheism, it is hardly offensive or unbiblical to say that our God can be worshipped – even if not properly through Christ – by Muslims under the name Allah.

Before I conclude this section, however, I want to explore one additional passage. In Acts 17:16-34, Paul addresses the people of Athens in the public marketplace. The occasion for the incident Paul instigates is the numerous idols the Athenian people have throughout their city. Paul’s actions attracted a lot of attention and put him in open, public debate with both Epicurean and Stoic philosophers. These philosophers accuse him of being a “babbler” and of proclaiming “foreign deities” because he was preaching the gospel of the crucified and risen Christ. His curious message attracted so much attention, that the sheer novelty of it gained him an invitation to speak to the public in the Aeropagus, a public forum where the elites of the city went to learn from esteemed teachers.

In his attempt to win over the philosophers and other elites of Athens, Paul chooses one of their idols – an idol to the “unknown god” – and uses this as a jumping off point. He chooses this monument to reveal to the Athenian people their own desire for a god they could not define. He reveals through this idol the God revealed in Jesus, the God who cannot be contained in images and idols. This God created all nations and placed within each of them a desire to “grasp for and find him”. This, he states, can even be seen in the words of Athenian poets.

Then Paul makes a very bold statement. He tells them that his God, revealed in Jesus, breaks the mold, quite literally. He taps into something within the Athenian community, the fact that despite all their gods rendered in so many different images and mediums, they still feel the need to recognize an “unknown” beyond it all. He even expresses that God can be patient with humans who are ignorant of him, but that a time comes when one must face the person of Christ – the one who reveals God for who he truly is – and make a decision. Many Athenians chose to follow Paul as a result of this speech.

This, to me, seems to parallel Dr. Hawkins approach. She chose to live out her faith (to give her faith “feet” as she stated in one interview) by choosing to recognize first a point of similarity. She then used that point, as Paul did, as a means of establishing a commonality with that community. Paul’s choice pointed others to the radical nature of Christ, to a god that may be known imperfectly by other means, but can only be fully understood in the cross. Likewise, with her actions, Dr. Hawkins has endeavored to live out what she believes to be the example of Christ for her neighbor. She has chosen to show what Christian love looks like in an act of solidarity, despite the ridicule and risk it poses to her own well-being.

Christ-Likeness

This brings me to my final category. As stated above, Dr. Hawkins claims to be living out what she considers to be a Christ-like love for her Muslim neighbor. This leads us to ask the question,

Are her actions truly Christ-like?

First, I want to expound upon something previously alluded. In Philippians 2:1-11, Paul calls the Philippian church to imitation of Christ. He admonishes them to share the same mind of Christ. This mind, for Paul, is made manifest on the cross. For Paul, the cross represents the pinnacle of Christ’s self-limiting. The moment when the one who was equal to God became a mortal, when he accepted death in faith of the resurrection. This man, the Christ, died in abandonment (Matt 27:46), he died beaten and abused, he died as a human for humanity – the very embodiment of sin itself (2 Cor 5:21). And yet, at his death, he entrusted himself to the Father in faith that he would be resurrected (Luke 23:46). This faith, the faith Paul explicates in Philippians 2 is the source of Jesus’ exaltation. He is lifted up and given a name above all names, the name that could only be YHWH itself.

But here’s the thing, Jesus did this by dying for humanity, among humanity, and as humanity. He did not die for the “peaceful” part of humanity, he died at the hands of a murderous mob while crying “Father forgive them” (Luke 23:24). He died on a Roman cross, a device so emblematic of Roman oppression and injustice that no Roman citizen could be executed on one, in order to show that the power of the Romans was, before the kenosis of God, nothing but foolish weakness. In his death, he called all of humanity to a different way, a better way regardless of their past ( (1 Cor 1:18-31).

In fact, Paul argues that Christ died once for ALL that, just as the firstborn of all creation has become the firstborn from the dead, so all might be called to God and share in his resurrection (Rom 6, Col 1). This can be further seen by considering how the Gospel narratives firmly root the cross of Christ in the tradition of the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 52-53. This tradition reveals the servant as one who is in solidarity with the people. He takes on their weaknesses, he embodies their ailments, he heals their afflictions and bears their iniquities. He is with them in the injustice they suffer and by his abuse, they are rescued. This servant, Jesus the Christ, is not revealed as a God removed but Emmanuel, the God who is with us (Matt 1:22).

This is the example, the mindset, that Paul calls the followers of Christ to have; and in doing so he mirrors the command of Jesus himself in Matthew 20:20-34. Jesus calls his disciples not to be those who lord authority and privilege over others, but to be servants of all. They are to imitate the example of the Son of Man who came “not to be served, but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many”. Jesus called his disciples to be humble as he was humble, to be in solidarity as he was in solidarity. And in case we might forget how his death ought to be viewed, the Gospel of John reminds us quite vividly. In 13:1-17, John begins his Eucharist scene not with the traditional formula of the other Gospels, but with Jesus stripped down to only his undergarment, kneeling on the ground like a common slave and washing feet. This was a God who got his hands dirty, who wasn’t afraid to touch lepers (Matt 8:1-13), to be sullied by bleeding women (Luke 8:40-53), or to embrace children (Matt 19:13-14). This was a God who didn’t rule his people, he served them, was them, died for them.

If Dr. Hawkins wishes to imitate Christ, she could do no better than to attempt to step into the situation of her neighbors, to embrace the vitriol they face and to stand firm as she is threatened, criticized, and mocked for her stance. She can do no better than to embrace the way of the God who “while we were yet sinners, died for us” (Rom 5:8).

Conclusion

It seems to me the discussion around this controversy largely centers in privilege. It is easy to critique the position of a woman who, as a way of embracing the life of Christ in the Advent season, chose to uphold herself as a symbol of love for and solidarity with her neighbor, when our standards for deciding what is “Christian” are reduced to “statements of faith” and “community covenants”. It is much harder to mount a critique when our paradigm is Christ himself.

So many of our statements are designed to decide who is in and who is out. They are designed to separate “us” from a “them” in order to establish a level of personal normativity. And that is what is at the heart of this issue. Dr. Hawkins has chosen to do something which erases such boundaries. She has decided that she has many neighbors, even those who might be considered by others to be enemies or outsiders – those who fit the bill of the proverbial Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37)! In fact, she has embraced the reality that loving those who are other, who might otherwise be labeled “enemy” requires us, like Christ, to stop being “us” and to step into the midst of and embrace “them” (Matt 5:43-48).

As I consider her actions, a final passage comes to mind. In John 4:1-42, a story Is told of Jesus visit to the Samaritan town of Sychar. The very setting of this story lets you know something profound is about to happen.

The history of relations between Jews and Samaritans was filled with bitter hatred[2], dating back to the split of the nation of Israel into the northern and southern kingdoms over issues of taxation. The king of the northern kingdom of Israel refused to recognize the Jerusalem temple of the southern kingdom of Judah as the ordained place of worship of Yahweh, so he built a temple on Mt. Gerazim in his own capitol city of Shechem, in the region of Samaria, for his people to worship instead. This temple would soon become a center of idol worship (1 Kgs. 11-12).

The northern kingdom began to see increased economic prosperity during the reign of the house of Omri in the 9th century BCE due to their willingness to make treaties with outside foreign powers, causing these tensions to only grow stronger. When the Assyrians conquered the north during the 8th century, they destroyed Samaria and deported many of its people, replacing them with foreigners. The north would then face many years of subjugation, as would the south, and many of the cities of both would be destroyed, as would the temples of both Shechem and Jerusalem. Eventually the Samaritans would be allowed to return to their region, but the north would never recover. In the 5th century, Ezra and Nehemiah began leading a migration of Jews back to Jerusalem to rebuild the city. These efforts faced strong opposition from the Samaritans and their political allies.

As a result, there were a number of conflicts between the two over the next several hundred years between Judah and Samaria. Eventually the Samaritans would rebuild their own temple at Shechem and claim it as rightful place for the worship of YHWH. By the end of the 2nd century, the hatred ran so deep, the leader of Judah, the Hasmonean priest John Hyrcanus, in 128, led a year-long military attack against Samaria, destroying their temple and laying siege to the region. During his reign, John Hyrcanus also conquered many of the regions that had previously made up the northern kingdom, expanding the borders of Judah to their greatest lengths since the time of the united monarchy.

In response, the Samaritans rebuilt their temple and, circa 100, released their own strongly revised version of the Pentateuch which reworded several key passages in order to place sole authority in the Samaritan religion and the only rightful place of worship on Mt. Gerazim. In the time of Christ, the region of Samaria still had many people of northern Israelite descent and the region itself was thriving under the rule of the Roman appointed client-kings.

This schism, which had once been fueled by political and religious segregation, had now become rooted in issues of race, as the Samaritans were no longer considered Jews, despite their common ancestry.

It is with all of this in full view that we read the story of the woman at the well. In fact, even built into the story, there are seeds which tell us of the expected animosity. For instance, when Jesus sits at the well and asks for a drink, the Samaritan woman is startled. To see a Jew in Samaria was one thing, but to have one speak to you and want to share with you, that simply did not happen (v. 9).

It is notable then that not only does Jesus ask to share her water, but he also offers to share with her the “living water” from God. While this continues the confusion initially, it leads to conversations about Jacob (they were at Jacob’s well) and common ancestry. Jesus then speaks with gentleness and love into the circumstances of her life, highlighting that she was likely a woman who had been rejected many times – as there is no mention of her husbands’ deaths and a woman filing for divorce would be highly unusual in ANE society.

Thus, as Jesus has spoken truth into her life that no stranger could possibly know, the woman recognizes Jesus as a prophet. She then turns the conversation to God himself. Jesus has promised a gift from God, yet the Samaritans worship God on Mt. Gerazim and the Jews in Jerusalem. Jesus perceives a question in her words and makes an incredibly profound statement:

[T]he hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship him (23).

Jesus fully recognizes that the Samaritans -sworn enemies of the Jews! – worship the same God, even in a flawed fashion, as the Jews. But the goes one step further! He also notes that the worship of the temple in Jerusalem is not what God truly desires. Instead, God is working towards a time (which is already at hand) when worship confined by specific spaces will no longer be the norm. God is breaking the mold, and, Jesus tells the woman, he himself is the promised Messiah who is advancing this cause.

This inspires the woman to find everyone she can and tell them of her incredible encounter with this strange man, Jesus, who claims to know God in a way no one else does, and calls others to join him as well. But this only happened because Jesus stepped outside the paradigm of animosity and antagonism. Jesus chose to obliterate the lines of denigration that separated the Jews from the Samaritans all together by integrating the Samaritan narrative into the greater story God was doing, even if the Samaritans at the time were worshipping a God they did not truly know.

Thus, it seems to me that Dr. Hawkins’ choice to spend Advent wearing a hijab is an appropriate gesture of Christ-like solidarity with her neighbor. Her actions call all Christians with a profoundly prophetic witness to consider what it truly means to be “in Christ” and to recognize that such an identity need not be defined against a denigrated “outsider” or “other”. Like Christ, she calls us beyond the antagonistic paradigm of “us” versus “them”. She invites us to walk in Christ’s shoes, to embody his ethic, and to carry his cross.

I cannot say whether Dr. Hawkins has violated the standards of Wheaton College, that is for others to decide. But I can confidently assert she has embodied the Gospel of Christ and abandoned the antagonisms which can only lead us away from Christ-likeness. In my opinion, one of these must take precedent over the other.

**Cover image from http://s1.ibtimes.com/sites/www.ibtimes.com/files/styles/md/public/2015/12/16/image-501584434.jpg**

[1] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, vol. 1 in Word Biblical Commentary (Thomas Nelson: Waco, TX, 1987) p. 316.

[2] Throughout this section on the history of hostility between Samaria and Judah (Israel), I will be drawing information from several articles. These sources are as follows:

Ron E Tappy, “Samaria”, pp. 1155-1159 in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (EDB) (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000).

Jeffrey S. Rogers, “Samaritan Pentateuch” p. 1159 in EDB.

Robert T. Anderson, “Samaritans” pp. 1159-1160 in EDB.

Stuart Lasine, “Israel” pp. 655-659 in EDB.

Sara R. Mandell, “Hasmoneans” pp.555-556 in EDB.

Steven L McKenzie “Judah” pp.744-747 in EDB.

For additional reading on the topic of Christians responses to Islam, see Miroslav Volf’s Allah.

The altar/pillar is not “just as much an idol” as an idol, you are confusing the place an idol would be put with the idol itself. No ancient Greek that I know of worshiped the altar/pillar, it was just a placeholder for possible further placement of an idol, which is what would be worshiped. P.S. The corresponding idea in Judaism was the ark of the covenant with the mercy seat, the Shekinah Glory rested about the mercy seat when present. No Jew would confuse the ark of the covenant and the mercy seat with the Shekinah Glory, they certainly understood that would be idolatry.

The Islamic God of Abraham is not the “same” as the Jewish God of Abraham for the simple reason that the Islamic Abraham is not the “same” as the Jewish Abraham. The 2 stories are incompatible, at most 1 of the stories can be correct. Once you pick one of the stories, this tells you the outcome about God. Furthermore, the Jewish God is a covenant keeper, while the Islamic God is seen to be so powerful that the Islamic God is not bound by covenants. Again, one must pick one or the other.

Does that mean that the true God would accept the worship of someone who does not have a correct conception? I believe so. But this does not mean the different conceptions are the “same” God, although there are a few attributes that overlap, for example, both see God as Creator, as Volf points out.

I am sure you aware that in some Moslem lands and in some groups of Moslems elsewhere women are required to wear the hijab or worse. In these cases, the hijab is a symbol of oppression. In fact, there is a group of Islamic women that do not wear a hijab as they see it exactly as a symbol of oppression and have asked non-Islamic people in general to NOT wear a hijab as a symbol of “solidarity”. In other words, if one is opposed to persecution and oppression, why not be opposed to all forms of it? In any case, Wheaton explicitly claimed that her wearing the hijab was not the concern.

On Jesus at the well with the Samaritan woman, Jesus did point out that the Samaritan worship was flawed while Jewish worship was not.

(Joh 4:21 Jesus said to her, “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem will you worship the Father.

Joh 4:22 You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews.)

One can see that the Samaritan Pentateuch has a substantial overlap with the Jewish Pentateuch, the Abraham story is the same and God is a covenant keeper in both. In Acts, the first people evangelized that were not Jews were Samaritans, this also indicates a closeness in their understanding of God to what the Jews believed, the Samaritans already knew a lot that was correct.

LikeLike

There is actually well documented evidence of pillar worship in many of the religions from which Greco-Roman religion borrowed its gods. In fact, even the Bible has fragments of what appear to be traditions of pillar worship in ancient Israelite culture. I would be sending you a lot of links to Google books here, but if you Google “Greek Pillar worship” there are several sources arguing the use of pillars on their architecture is rooted in their early religious practices of pillar worship.

That being said, you’re argument is practically a non-sequitur. I said the pillar stands in for the god in question. The Greeks/Romans didn’t believe their gods were contained by idols. They believed they were controlled by them – that worshipping an image of the god appealed to that god’s vanity and thus they would be more favorable toward the worshipper. Thus, whether there was an statue atop it or not, the point of the pillar was to let the “unknown god” know they were still worshipping him. Functionally speaking, from the narrative details we have, the pillar served as an idol – a proxy for the god reminding the people to worship in order to procure favor.

The issue with your equation to the mercy seat is that God himself – not an image of him – was believed to be present there. The mercy seat was an earthly correlate to the heavenly throne. The entire temple was a microcosm of creation – images of heaven and earth and even Eden were built into cultic practices. The holy of holies was believed a direct connection to the judgment seat of God, the mercy seat is actually more accurately a mercy stool, a translation that seems confirmed b Isaiah’s vision of God which seems to indicate his feet resting upon the mercy seat. (for more on this, read Carol Meyers excellent commentary on Exodus).

The Jews refused to even recognize their ethnic ties to the Samaritans. It was against the law to eat with them or share anything with them. They were treated as Gentiles (even Jesus referred to the Samaritan leper as a “foreigner”).

The many wars between Judah and Samaria/Israel made for tension. The opposition of the Samaritan king to the rebuilding of Jerusalem created more tension. And the raising of Samaria and destruction of their temple in an attempt to restore “true Israel” also demonstrates the pure animosity.

It is hardly accurate to say that the Jews thought the Samaritans “had it mostly right.”

You still are insisting on a definition of same that is entirely without nuance. And as I went over in my other article, both Ryken and Jones made gender specific comments.

Not to mention the words of Michael Mangis, the diversity committee, 20 Wheaton alum political scientists, and 78 faculty.

People who were charged with investigating the incident and given full access to all information said this was about race and gender.

Also, the factoring of pressure from Frankln Graham and his history of xenophobic and anti-Islamic rhetoric calls Wheaton’s statements into question.

Lastly, you treat opinions on hijab as monolithic. It does not mean the same thing to all Muslims. Further, something being a symbol of oppression has zero to do with whether it is an effective symbol of solidarity. If it is a symbol of oppression and abuse, it a no less so than the cross.

In whatever case, we can agree to disagree. The issue has reached an odd resolution, but it has been resolved.

LikeLike

So many pearls of wisdom in here.

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike

Act 17:23 For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription, ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you.

An altar is not an idol, as you claimed in your article. In the case of a pagan religion such as at Athens, it was a place where an idol would be put, but since the idol/”god” was unknown, they decided to leave it empty, as any guess about what it might be might be wrong and insult the unknown god, which was the opposite of the intent in the first place.

Paul was grossed out by all the idols he saw in Athens. He finds an entry point to present the gospel to them by finding an empty altar to an unknown god where an idol would normally be. It is always preferred to start discussions between believers and non-believers with grace and points of agreement or things the non-believers are familiar with, he certainly did not start off with how grossed out he was, although that was the case. But at some point he brought up points of truth.

Act 17:30 The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent, …

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Donald. Was wondering when you would show up 🙂

A few critiques of your argument.

The wording of 17:16 does not say Paul was grossed out. In the Greek, it states “the spirit within him was angered/provoked”. Those are distinctly different reactions.

2) Quick question, how do you define idol? If it is only a graven image, then you are technically right I suppose. But if an idol is something which stands in the place of true worship of YHWH than the pillar was just as much an idol. Whether an image stood on it, it was a deviceby which the Athenians sought to worship a deity. Paul even describes the worship of the Athenian people (including that of the unknown god) as worship of gold, silver, and stone – the uplifting of human imagination over the creator who imagined them (seems reminiscent of Romans 1 to me). He is calling the foundation of Athenian worship idolatry. For me, if they used the pillar to worship a god, then the pillar was an idol in and of itself.

3) Paul didn’t just speak of an unknown god and use Christ to redirect this to the true God. He quoted ancient Greek poetry that was written to worship Zeus and redirected it. He argued it actually points to the God of Christ. Paul use their own literature to say not simply that they were idolatrous but that the very worship of their own gods, in all reality point to the only true God – even if imperfectly. Again, echoes of Romans 1 here.

4) Since I directly referenced 17:30 and have stated that God can only be properly worshipped, properly revealed in Jesus Christ crucified, I’m not sure what you think this verse proves.

I haven’t denied Jesus as God anymore than Hawkins did. I haven’t argued Allah as the way to justification before God or the promise of resurrection. I have only stated our God can be worshipped imperfectly by those seeking to discover the true creator god.

LikeLike